From being rejected by NASA three times to almost breaking the Hubble Space Telescope, Mike Massimino talks about the value of perseverance – which has gotten him into NASA and made him a New York Times bestselling author.

Former NASA astronaut Mike Massimino is known for many things. Not only has he flown two space missions, the first aboard the space shuttle Columbia in 2002, and the second aboard the Atlantis in 2009, but he was also the first person to ever tweet from space, the last person to work inside of the Hubble Space Telescope, and, along with his crew mates, is responsible for setting a team record for the most cumulative spacewalking time in a single space shuttle mission, logging a total of 30 hours and four minutes during the course of four spacewalks.

After almost two decades with NASA, Mike left the space agency in 2014 for a full-time position at his alma mater Columbia University in New York. Since then, he’s written a New York Times Bestseller, Spaceman: An Astronaut’s Unlikely Journey to Unlock the Secrets of the Universe, and even nabbed himself a six-time recurring role on the hugely popular CBS sitcom, The Big Bang Theory. We sat down with the rocket man himself to learn more about his journey from being a nerdy kid with bad eyesight to eventually making it to space only to fumble, but then persevere through that now famous blunder.

Despite his many accolades, not to mention his 1.22 million followers on Twitter, Mike Massimino is an incredibly humble and, forgive the pun, down-to-earth guy. “I still can’t believe I had the chance to be an astronaut,” he begins, wistfully. “I’ve always liked sharing stories about my time up in space with the public, probably more so than some of my colleagues. It’s just the greatest job in the world, and I enjoy telling people just how extraordinary that experience was. I’d read other astronaut books and enjoyed reading them, but I didn’t know if my story was something that people would want to read.” It wasn’t long before Mike realised that there was an audience for his book – a big audience in fact. So, in 2014, along with the help of acclaimed author Tannor Colby and host of The Daily Show Trevor Noah, he began writing his bestseller.

But let’s go back a bit, to the year 1969, the year that Neil Armstrong first walked on the moon and a seven-year-old boy in Long Island first dreamt of becoming an astronaut. A reluctant realist, the young Mike didn’t start off convinced he could make it. “Though the interest never left me, I just couldn’t believe that being an astronaut was possible. It was during my senior year at Columbia University that a movie called The Right Stuff came out, rekindling all those emotions I had as a very small boy.”

“I thought Neil Armstrong, all those guys, all the moonwalkers, they were just the coolest,” he remembers, grinning. “I just knew that that’s what I wanted to be. They were explorers. They were like the epitome of cool in my mind.”

By this time, it was the mid-1980s. The space programme was beginning to change, meaning that it wasn’t only involving military test pilots like in the beginning, but now also scientists and engineers. Engineers like Mike Massimino. “At Columbia, I was an industrial engineer. I think I was actually quite lucky in that, had I known prior to studying that I wanted to be an astronaut, I might’ve picked a subject that wasn’t for me. Instead, I just did what I liked. After that, I was able to get accepted into mechanical engineering at MIT as a grad student. In my mind, the key to success is not to force things. If you do what you are interested in, it’ll lead you down the right path.”

Armed with his new career aspirations, Mike began the gruelling NASA application process, a process which would take up the better part of a decade. “I got rejected by NASA three times. The first two, I got rejected with a letter back saying no, the third time I applied I got through to the final round only to then fail the eye exam.” Not one to back down from a challenge, Mike then set about literally training himself to have better eyesight. “They declared me medically unfit. If they had said there was someone better for the job, I might’ve let it go, but they essentially disqualified me on the basis of my eyesight, and I wasn’t going to give up because of that.”

After years of patience and persistence, Mike was finally selected to be a NASA astronaut candidate in May of 1996, leading to him spending exactly 571 hours and 47 minutes in space. When asked why, in the face of so many obstacles, he didn’t give up on his dream, he replies simply, “Well, if you give up then you’re not going to be successful. And I could live with not being successful, but I could not live with myself if I didn’t try.” And what does he say to those naysayers that question why even trying if you know it’s impossible? “I think there’s a difference between something being impossible and something being unlikely. Unlikely means that it’s tough and it’s probably not going to happen, but it’s still possible. And the only way things become impossible is if you don’t try.”

It was during his second and final flight mission in 2009 that Mike sent the first ever tweet from space. It’s also when he nearly broke Hubble. “During my last spacewalk we encountered a problem – well, I caused the problem really,” he recalls. “I stripped the screw that I was supposed to remove and we were running out of time. It was horrible. I was living in a nightmare. I didn’t think that there was any way that we were going to fix it. But one thing that I learnt in training is that no matter how bad things seem to appear, you can actually make it worse. There were a lot of things I could have done to make it a life-threatening situation or break something else. So, I told myself to just hold on a second, and not make things worse.”

What would the implications have been had he failed in his mission to fix Hubble? “Oh, that would have been bad,” chuckles Mike. “We had practiced doing this for a very, very long time. We started training for this about five years ago, and it was pretty much the most intricate repair work we had ever tried to do. On top of that, we had developed over 100 tools for this mission, at great expense. So many people had put their time into this, we’d trained so hard, and so much money was spent to get this repair done. And then the science would have been lost as well.”

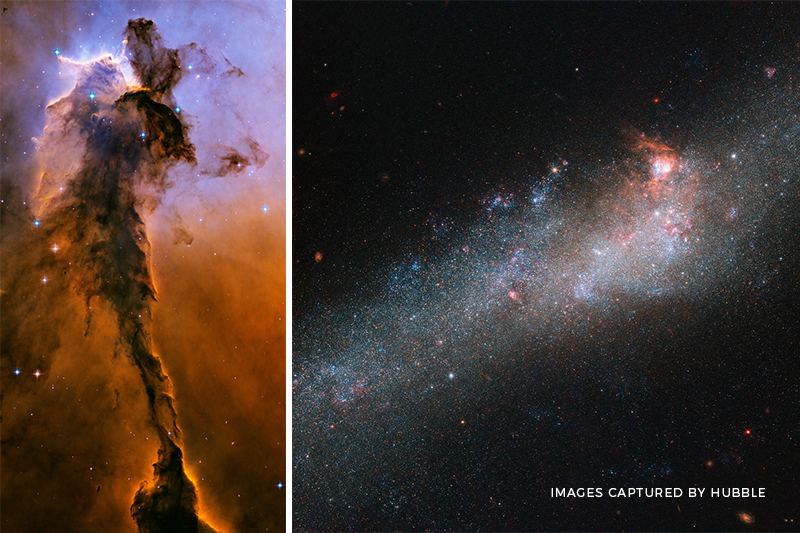

Luckily for us, he didn’t give up. To this day, Hubble remains to be the only telescope designed to be serviced in space by astronauts, and it continues to make amazing scientific discoveries like pinning down the age of the universe to discovering four of the five moons that are currently known to orbit the dwarf planet Pluto. As recently as a year ago, the front page of The New York Times confirmed the discovery of a planetary system that might have Earth-like planets. “Usually when I see something like that I go, ‘Was it Hubble? And What instrument on Hubble found it?’ Someone sent a later article to my spacewalking buddy Mike Good identifying it as being the exact spectrograph we fixed on Hubble. So, it’s still working and making these great discoveries, and if we hadn’t been able to recover from that and our team didn’t save the day, we wouldn’t know these things.”

Throughout our conversation his boyish love for space remains palpable – infectious even (five minutes with the guy and you might even consider buying a USD 20 million seat on the SpaceX Dragon). When asked what, in his opinion, is the hardest thing to describe about space, Mike replies, “I think the emotional part of it. You can talk about what it took to repair the telescope, and the tools we used and other technical details quite easily, but the emotional part – like how extraordinary it is to be up there and just how beautiful the view of our planet was – that was hard. You just never get numb to the emotional feeling you get when you’re up there. Every time you looked there was something different to be awed by. It’s like looking at a loved one and then looking away for a while, then looking back and being hit by that kind of emotion. That’s the way it was for me.”

Related Articles

NASA’s First Australian Astronaut Shares His First-Hand Experiences in Space

7 Self Care Tips from an Antarctic Polar Explorer

Off the Grid: Polar Explorer Ben Saunders Defines His Limit-Defying Career