Navi Medical Technologies is providing real-time insights on newborn catheterisations to speed up the delivery of life-saving drugs. Discover how they managed to turn a classroom idea into a revolutionary medical device for newborns here.

Umbilical venous catheterisation is an emergency procedure performed on premature and critically ill newborns who require life-saving drugs to be delivered via a catheter (a thin hollow tube) through the vein of their umbilical cord. At least 400,000 procedures are performed worldwide, but, with no way to locate or visualise the tips of these catheters in real-time, 40% are inserted into babies’ veins incorrectly, causing pain and distress.

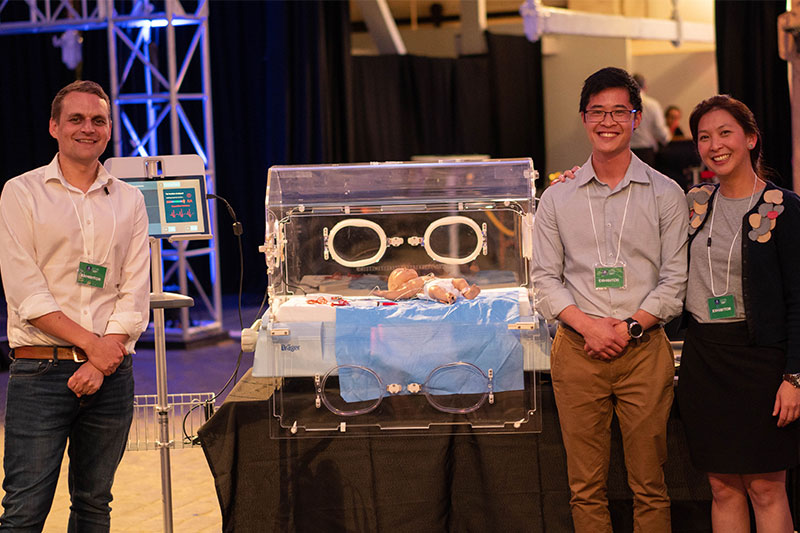

Victoria-based medtech startup Navi Medical Technologies hopes to change that. What started in 2016 as a classroom idea during a BioDesign course at the University of Melbourne has since become an award-winning company devoted to the singular task of building and commercialising a medical device that helps doctors track the location of a catheter tip in real-time without an X-ray. This means reduced X-ray exposure, faster delivery of life-saving drugs and improved workflows for busy doctors in intensive care units. Their technology’s potential has been hailed across the medtech industry as revolutionary, with Navi Medical Technologies receiving both the first prize in the Startup Vic HealthTech Pitch Night and the Grand Prize at the Pediatric Device Innovation Symposium in 2017. They’ve also completed several prestigious medical device accelerators, including The Actuator, Australia’s National MedTech Accelerator, and TMCx, a world-renowned accelerator in the Texas Medical Center.

Shing Yue Sheung, one of Navi’s six co-founders and a Forbes 30 Under 30 Asia entrepreneur, sat down with Hive Life recently. Born a premature baby himself, Shing reflects on why so few pediatric medical devices cater to newborns, shares his insights on the Melbourne medtech scene and divulges how his team are effectively treating the most vulnerable patient population in the world.

As someone with a background in commerce, what inspired you to venture into pediatrics?

So I started my pediatrics journey in a slightly unconventional sense. Biomedical engineering, the bridge between medicine and devices, has always really interested me, but the pathway to becoming an engineer at Melbourne University is quite unique in that you have to do a Master’s degree to qualify. I wanted to work on as many things as possible while still becoming an engineer, so I chose the pathway of doing a Bachelor of Commerce first before making the leap into an Engineering Master’s. Where things got pretty interesting was when I did an exchange semester in Zurich, Switzerland. That gave me my first taste of innovation and hackathons outside of Melbourne. By the time I came back to Melbourne, I was itching to do something interesting myself and that’s when I enrolled in the Biodesign Innovation programme.

The Biodesign Innovation programme, taught in conjunction with the Melbourne Business School and the Melbourne School of Engineering, matches MBA and bioengineering students with doctors to learn about the medical device commercialisation process and identify unmet clinical needs. I teamed up with fellow engineering student Mubin Yousuf, MBA students Brad Bergmann, Wei Sue and Alex Newton, and also Dr Christiane Theda from the Royal Women’s Hospital in Melbourne. A topic that kept recurring in our conversations with clinicians was the need for better real-time localisation of umbilical catheter tips in newborns. Initially, we looked at concepts in orthopedics or cardiovascular diseases but, in the end, we decided to focus on pediatric medicine because we felt like the impact we could have on a newborn’s life was exponentially greater than if we’d impacted someone’s life later on. As a premature baby myself, I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for the care I received back then, so part of this is really giving back to hospitals and clinicians, and to the next generation of premature infants as well. With that in mind, we began working on the concept which is now our company today: Navi Medical Technologies.

You might also like Robot Therapy: AI Comfort for Elderly Patients

In layman’s terms, what medical problem is Navi Medical Technologies trying to solve and why is it important?

Right, so the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that around 30 million premature or sick babies are born each year, and a large portion of those patients require urgent vascular access care. What this means is, they require life-saving drugs, nutrients and medications to be delivered to them so that their organs can develop further. One of these specific procedures is called an ‘umbilical venous catheterisation’ (UVC). That’s where doctors in newborn intensive care units insert a thin flexible tube called a ‘catheter’ – or a ‘central line’, more specifically – into the patient’s umbilical vein. The goal is to position the tip of this catheter at precisely the right part of a baby’s body or risk severe discomfort. Under the current standard of care, a catheter tip beneath the skin level cannot be visualised unless an X-ray is used, which takes time and exposes the newborn to radiation. As a result, misplacements of the tip occur around 40% of the time during a procedure. But, even with perfect line fixation, the tip can still move around post-treatment to potentially dangerous locations inside the body. Around 50% of correctly placed lines migrate within the first seven days, so it’s really a compounding problem that stems from a lack of real-time feedback on the catheter tip.

What solution did you come up with?

We’re developing a medical device concept called the Neonav, which uses machine learning and electrocardiogram (ECG) signals to accurately track the location of a catheter tip in real-time without an X-ray. If a newborn needs a UVC, Neonav enables doctors to position the catheter correctly and confidently on the first attempt. Our device also monitors for tip migration in the days after a procedure so that corrective action can be taken if necessary. The analogy we sometimes like to use is a car’s parking sensor where it shows on-screen whether a tip is getting closer or farther away from the ideal spot. That’s the visual indication we’re providing at the moment.

On your website, it states that only 15% of pediatric medical devices are indicated for use in newborns. Why is that the case?

So that’s a statistic from a big study conducted by the FDA (US Food and Drug Administration) on high-risk medical devices. Of all FDA-approved medical devices, very few are actually indicated for the pediatric population. And even then, the vast majority of those devices are labelled for patients aged 18 and above. See, the FDA defines ‘pediatrics’ as any patient between the ages of zero and 21, which is quite a large range. So even within a tiny subset of pediatric devices, only around 15% cater specifically to the needs of neonates (birth to 28 days) and infants (29 days to 2 years). That’s a subset of a subset.

The FDA found that the reason why it’s so small is because of the return on investment. The ROI of pediatric devices is perceived to be lower as it’s not only a challenging market, but also a relatively small one. When you think of the percentage of patients aged between zero and 28 days old, then compare it to the adult population of 21 years and above, that’s a significantly larger population that can be treated. So based on market size alone, a lot of major medical device manufacturers simply don’t touch pediatric patients, let alone neonatal ones.

So how did you pitch your idea in a way that made it viable to investors?

The way we pitch the Neonav to investors, grants and key decision-makers is by highlighting this gap in the market. We didn’t have a product ready when we started winning competitions in China, Australia and the US – just a really robust foundation of the clinical need and a support network that cared as deeply about this issue as we did. The old saying is that children aren’t just ‘little adults.’ However, a lot of device manufacturers use a top-down approach where solutions are developed for adults and then scaled down to neonates and infants. But, that often doesn’t work well because children have their own unique physiology and anatomy with regards to heart rate and organ size development. It’s much wiser to take a bottom-up approach where you start with the hardest patient population first then scale upwards. And that’s what we’re doing.

Most startups tend to have one or two co-founders, but Navi Medical Technologies has six. What’s it like having so many co-founders?

Yeah, it’s rare for sure. I think the key here is that each of our six co-founders covers the three important bases of a medtech business: engineering, business and clinical. In terms of how we’ve stuck together, we just get along really well. A lot of courses around the world use Myers-Briggs or other personality tests to assign team members, but ours was formed organically. We make each other laugh, we have the same interests, and we communicate really well despite being a diverse team. We’re not sure if it’s luck, but it’s something we’re incredibly proud of.

What has the reception been like? Do you foresee any potential barriers to adoption?

We still need to get product approval, but even with the early prototypes of Neonav, we’ve been able to demonstrate that our device can identify specific waveforms and determine where a patient’s catheter tip is – and clinicians seem to love it. We’ve interviewed over 80 clinicians across Australia, Europe and the US, and they’ve all demonstrated goodwill and a consistent need for neonatal solutions.

I think one of the biggest barriers would be inertia in the current standard of care and clinicians not wanting to deviate from what they’ve been taught. Neonatal Intensive Care Units are caring for the most vulnerable and critically ill patients so this standard of care exists for a reason. Our philosophy is that we’re creating an accessory to the existing procedure that supplements the skills of a clinician. And that’s something we’ve been very careful about. But what we’re also seeing is similar technologies to ours being introduced to adult procedure guidelines. My dream one day is to see our device and our techniques being implemented in neonatal guidelines. That would be a huge dream of mine. It’ll certainly take a lot of time, but I think that’s when we’ll know we’ve really overcome these barriers.

You were on the coveted Forbes 30 Under 30 List. What was that like, and to what do you owe your success?

I think it was more validation than anything else. This came at a point in time when we were still deciding whether Navi was something we wanted to pour absolutely everything into. And I say this as a joke, but being on the Forbes list reveals my true age. Sometimes I wear different glasses to different meetings to try and make myself look older, but I think it’s mainly proof that I’m young, I’m motivated and I’m coachable in an industry that is changing all the time. I may not be the smartest or most experienced person in the room, but this is something I really care about.

In terms of success, having a strong team that covers different aspects of the business is super important. My co-founders keep me sane – I honestly can’t imagine working on this company as a sole founder. But, I think it’s also about making mistakes and failing quickly. One thing we often say at Navi when identifying clinical needs is, ‘The only thing more dangerous than not talking to any clinicians is only talking to one clinician.’ As an engineer, it’s a lot easier to just stay inside and code, but something I’ve learned is that it’s much more beneficial to bring your concept outside and have people poke holes at it, even if it feels scary or confrontational at times. We really believe in the iterative approach and that growth mindset. It’s okay to make mistakes, as long as they’re not irreversible, and you can improve on them to come out stronger on the other side.

What’s next for Navi Medical Technologies?

Future plans for us would be completing the feasibility phase of our ongoing clinical study in Melbourne and raising more funds once we’ve demonstrated strong clinical evidence. We’ll also need to perform detailed device design for product registration. As for specific timelines, it’ll still be a few years away but, of course, with medical devices, we have to be extremely careful and risk-averse. So right now, we’re taking all the steps we can to meet every single standard possible to ensure our device is safe and effective for use.

To learn more about Navi and follow them on their journey, visit www.navitechnologies.com.

Related Articles

Vietnam: The Latest Hotspot For Medical Tourism