It’s not shown on TV, but every day, millions of sharks are killed for their fins. We sat down with renowned shark conservationist Dr Austin Gallagher to dive into the dark side of a shark’s life, a story hidden beneath the waves.

Sharks have been around for over 400 million years. And yet, the animal that has outlived even dinosaurs is now under unprecedented threat. Despite them only being responsible for less than 10 human deaths a year, we kill up to 100 million sharks annually. Most of them die because of overfishing and shark finning, a process of removing fins from sharks and discarding the rest of the body. “It is one of the greatest environmental issues you’ve never heard of,” says Dr Austin Gallagher, who recently gave a talk as a guest speaker at Hong Kong’s Royal Geographical Society on shark conservation.

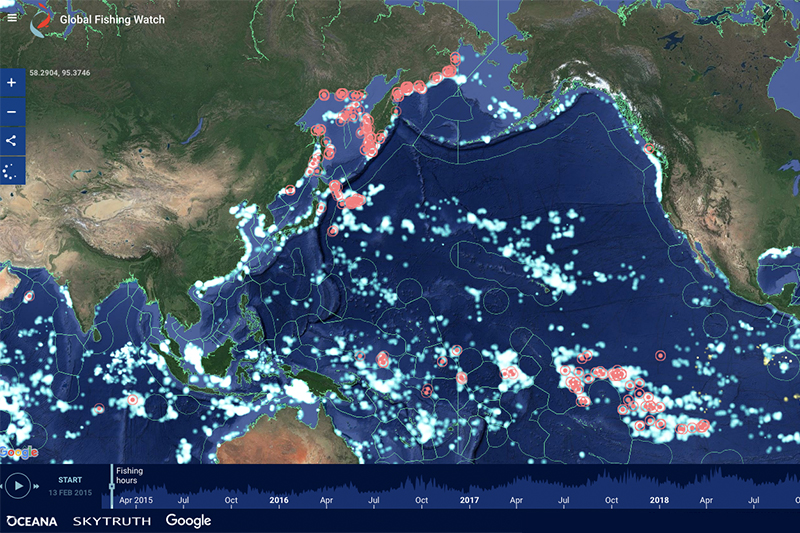

The first American marine biologist to be named an honouree in “Forbes 30 under 30” in the science category, Dr Gallagher is a social entrepreneur and man who has dedicated himself to tracking the secret life of sharks. “We are now tracking the movements of 2 blue sharks,” he begins, showing us a satellite map of a beautiful multicoloured visual. Created by international advocacy group Oceana in collaboration with Beneath the Waves, a non-profit research organisation founded by Dr Gallagher in 2012. Published on the website Global Fishing Watch, the map gives public free access to the critical data of commercial fishing activities and how they intersect with the high migratory shark species.

“These are all fish boats,” Dr Gallagher explains, pointing at the fluorescent blue dots clustered around the Atlantic. Amid them are meandering lines of pink, orange and green, which indicate the activities of the tagged sharks. “What we found is 60% overlap between fish boats and our sharks. Within these few days, we’ve recorded 36 million instances of actual boats and sharks coming within 500 meters of one another. It’s a sea full of hooks, there’s no way these sharks can swim through.”

Bycatch, meaning unintentional catches of non-targeted marine life, is one of the biggest problems facing sharks today. In commercial fishing, nets and baited fishing lines often stretch for miles, indiscriminately capturing all manner of life, including thousands of sharks. The fins of these sharks will be cut off, their carcasses either made into meat or simply discarded into the ocean to drown or bleed to death. According to Oceana, dusky sharks alone have experienced an 85% decline in population due to overfishing and bycatch. “Some of our sharks have been killed by boats, a lot of those fins are coming here to Hong Kong,” says Dr Gallagher.

Hong Kong is the world’s largest shark fin importer – even given a 50% drop in imports since 2007. Data from the WWF Hong Kong office shows the city imported 4,979 tonnes of shark fin last year. Most end up in shark fin soup. “65 million blue sharks are killed every year for their fins,” says the conservationist. “It’s insane. That is literally the most exploited large animal on the planet that’s not a cow.” And they’re particularly vulnerable to attack. “Sharks are slow growing and slow to reproduce. They’re sensitive, like humans.” A shark could take up to 33 years to reach maturity, some species only have two offspring in their life, with others only reproducing every two years. And, as the doctor sees it, the urgent key to saving them from extinction is to rebuild the public’s respect for sharks, something under threat not least thanks to a certain movie. “Following Jaws, many people were scared of sharks and thought the only good shark was a dead shark,” Dr Gallagher recalls.

His shark tracking initiative hopes to reverse some of that damage. Leading a crew of multidisciplinary scientists from Beneath the Waves, the researcher has had satellite transmitters fixed to over 40 sharks around the Bahamas and the US since 2012, covering a range of species. “I get excited by the fact that we can always learn something new every day. Science is about freedom, and what excites me is that I have the freedom to work on the things I want to work on, which is incredible,”Dr Gallagher enthuses. “I catch the animals to tag them and study their behaviour, but I also get to snorkel with them and swim with them.”

When he’s not on the boat waiting for sharks and analysing statistics, Dr Gallagher spends his time working with tech engineers, oceanographers, entrepreneurs, and international NGOs to help spark new conservation strategies and raise public awareness. “Creating teams is really powerful because you create this energy around a common goal, and everybody wins. The camaraderie makes it way more fun.” The same applies to his fundraising. “People believe in the mission, but people invest in people.”

And people like us remain essential to the future safeguarding of both the shark species and our planet. “Don’t eat sharks,” says Dr Gallagher. “We have to remember that everything we do is a choice. We have a choice to make more sustainable decisions in the long term, whether it’s how much plastic we use or how much meat we eat – all these things will have an impact on our planet. If we can eat more sustainably, live more sustainably, we’ll have a lower carbon footprint on an individual level. Little things matter – people just need to be reminded of that.”