Professional speaker Mark Henick takes us through his battle with depression – from being a suicidal teen to becoming a highly sought-after mental health advocate – and provides his insights on persevering through mental illness.

Mental health is never an easy topic to broach but with suicide becoming a leading cause of death among young people, things need to change.

At the brink of mental collapse, a-then-15-year-old Mark Henick was determined to end his life. Flash forward to the present, and he’s travelling the world, sharing his story, and breaking stigmas along the way. As a public speaker, mental health counsellor, policy influencer, and ex-president of Canada’s Mental Health Association wing, Mark has worn many hats in his endeavour to open minds and create change.

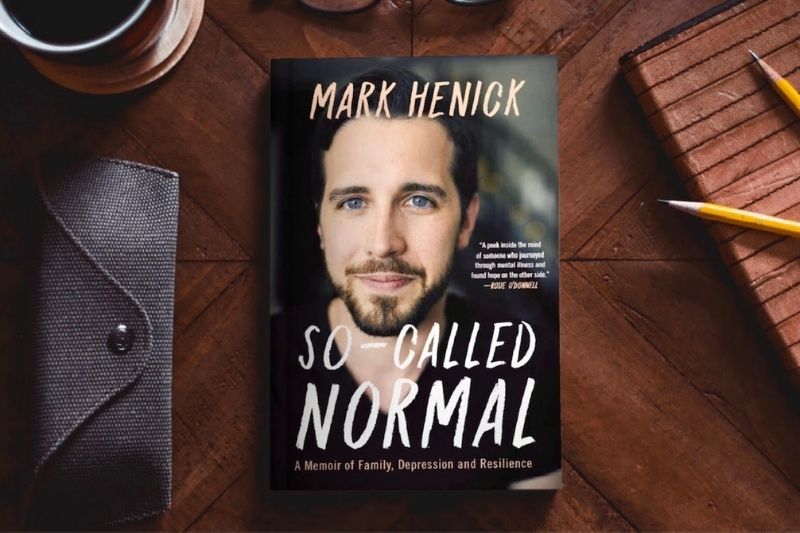

As he gears up for the release of his tell-all memoir, So-Called Normal, Mark sits down with us to talk about his journey, the lasting effects on mental health the pandemic will have, and how to persevere and not become a victim of your circumstances.

From a suicidal teen to a mental health strategist and advocate, you’ve come a long way. What was the journey like?

“Opening up and speaking about mental illness saved my life”

When I was 10, I first started experiencing symptoms of what I now know as depression and anxiety, going on to becoming suicidal at 12. I was in and out of hospitals more than half a dozen times, with increasingly dangerous attempts each time. In what would become my final attempt, I was about to jump off a bridge, when a complete stranger pulled me off of the edge and saved my life. I had a vague memory of the stranger but I didn’t see his face, I didn’t remember his name or anything else about him. I just remembered that he was wearing a light brown jacket, everything else had faded away.

It was at that moment that I had a small change inside of me – I wanted to be like that guy who reached out and saved my life. That’s how I got into advocacy, I’ve been opening up about my experience with depression, major depressive disorder, social anxiety disorder, and multiple suicide attempts as a teenager for many years now.

I think the most rewarding part of this journey was realising that this illness didn’t have to define me. It was when I was able to finally let go of that identity, that I was actually able to move on from it.

Did you eventually end up tracking that stranger down?

I did a TEDx talk where I spoke about this story, about him – he was still just a stranger at that point. I didn’t even fully know if he was real, you know. I didn’t know if I had just made him up because I needed a saviour figure in my mind. When the Ted Talk got big and people started telling me that I was that stranger for them, I felt like an imposter. I didn’t even know my whole story, so who am I to tell these people how to live their lives? This prompted an impulse of trying to find out who this person was, or if they were even real to start off with.

After my story went viral across Canada, I started getting calls from people who said they knew that stranger – his name is Mike by the way. That’s how we ended up meeting each other. He talked to me and even met my family. He told me how scared he was that night and that when he saw me let go of the railing, he just reacted. He never knew if I just went back the next day and finished what I’d started. He had wondered what had happened to me for more than a decade – until he came across my TED talk.

Let’s talk about the elephant in the room. What impact has the pandemic had on global mental health?

I think back in March and April, there was a rampant trauma response. Especially in the initial part of the pandemic, it came as a shock to most people where everyone was just experiencing profound grief over all the things they had lost at that point.

More than six months into COVID-19, and my concern is now around the isolation and the trauma that stems from it. My worry is that people are going to stay stuck in this headspace. Resilience is all about how people bounce back from adversity but if they’re not allowed to bounce back, if there’s a barrier of some kind that’s keeping them from bouncing back, then it can become more ingrained. We’re already seeing it becoming increasingly difficult for people to “snap out of it”, move on, or adapt. People aren’t as resilient when the circumstances around them are so stressful and difficult.

So I think that we’re going to continue to see increasing rates of mental health problems and illnesses, especially depression and anxiety and very likely suicide as well.

Is enough being done about mental health awareness?

Yeah, I think we’re definitely making some progress. In the last decade, we’ve been having really interesting conversations. Though, I would characterise them as quite superficial since they don’t really get into the meat of what mental illnesses are and what mental health means. It is, however, better than nothing. At least people are talking. We see more celebrities than ever speaking up about their own experiences, and that does count.

We know that millennials and those younger are much more likely to reach out for help than the older generations. That’s the whole point of stigma reduction and awareness raising – we need to increase this help seeking behaviour. If people don’t feel that others are going to call them crazy, and if they feel comfortable with their mental health, then they’re much more likely to actually get help when they need it. That’s the point.

However, the problem is when they get to that stage – that’s where we still have yet to grow. The service system of people who reach back when somebody reaches out still has a long way to go. Governments still need to invest more money in mental health and mental illness services and societies still need to invest in these issues more. We haven’t quite cracked that yet.

How can someone cope with depression during extended periods of isolation and uncertainty?

1. Acceptance and change

One of my personal practices comes from a type of therapy known as dialectical behaviour therapy, which is a principle of acceptance and change. Much of our struggle actually comes from the friction between what is happening to us and our acceptance, rejection, or resistance to it. It’s the fight, not the event that causes us so much trouble.

Acceptance doesn’t mean you need to like the event, or that you want others to experience it. It doesn’t even mean that you want it to continue. It just means that it is what it is. That you recognise that it sucks, but that’s okay. It’s allowed to suck because it is what it is.

My firm belief is that human beings are inherently resilient. Our brain’s primary imperative is to keep itself alive so our mind can do incredible things to ease our pain, if we allow it to. Practising both radical acceptance and embracing the change, rather than resisting it and causing friction, is what will help you get through the variety of difficulties in your tough times – it certainly helped me.

2. Help is readily available, you just need to reach out

An unexpected silver lining of the pandemic, if there are any, is that it has forced the virtual healthcare space to really thrive in an incredible way. It has become easier than ever to connect with a mental health professional. There are platforms that are readily accessible for a wide range of mental health professionals across the spectrum but people need to make the choice to put themselves first – to take care of themselves and to engage with these services. It’s an investment in yourself. And I think that you need to make that choice to take care of yourself.

3. Don’t get demotivated by relapses

In the initial days of my recovery process, I used to relapse once a year, usually in spring. Recognising that you have a mental illness, getting treatment, and then getting better – it’s never a linear kind of process. That’s just not how recovery happens.

Eventually, I got to know my patterns and rhythms a little bit better. Something clicked and every time I started to relapse, I thought to myself, you know what, I know this is coming. I’ve been here before. I’ve gotten out of this countless times before. Sure, it’s going to suck. It’s going to be terrible but I’m going to get through this again, because I have every other time. Everybody experiences bad days, relapses are just a part of the recovery process.

4. Practice physical distancing, not social isolation

Going into the pandemic, we already had a wide range of tools to be social without having to physically be next to somebody. We need to maintain contact with people. We can’t perpetually live only in our heads. Reaching out to people on social media, making it a point to make more phone calls, make it a conscious choice to find ways to maintain social connection with people.

This rings especially true if you are trying to help a loved one dealing with depression. Talking to people is also the best form of healing. A core fear when you’re severely depressed is that nobody cares about you. If you have deep meaningful relationships with people, it disproves that theory. They don’t need a fixer, they need a good friend – someone who’s willing to reach out, be empathetic, and connect with them whenever possible.

More about Mark Henick

Mark is the principal and CEO of boutique consulting firm Strategic Mental Health Solutions, which works with organisations across Canada to develop wellness-inducing practices in the workplace. He can also be seen on numerous Canadian media channels as a commentator and public speaker on mental health awareness, the inefficiencies of the health care system, and suicide prevention. He hosts 2 podcasts, So-called Normal and Living Well, available on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

Related Articles

One Man’s Journey: Changing How We Talk About Men’s Mental Health

Mind Medicine Australia: Could Psychedelics Solve Our Mental Health Crisis?