Acclaimed Japanese designer Eisuke Tachikawa, the founder of Nosigner, is sparking innovation with his avant-garde designs. His products have since made their way to 8 million households across Tokyo.

Just 40 hours after the Great East Japan Earthquake ravaged the coast of Japan in 2011, award-winning designer Eisuke Tachikawa launched a new project: OLIVE, a wiki-style site that gathered crowd-sourced designs to help the victims affected by the disaster. Little did he foresee that it would spark a whole movement – one that morphed into a nation-wide project lauded as the largest disaster prevention plan in administrative history. Today, the designer’s iconic disaster manual, ‘Tokyo Bousai’ (Disaster Preparedness Tokyo) has been distributed to more than 8.3 million households out of the 9.2 million that live in Tokyo – something he sees as a clear example of design leading innovation, rather than the other way round. “I believe that we’re at a point in human history where, rather than social infrastructure leading design, we have design taking unprecedented authority,” says Eisuke. Read on to discover why.

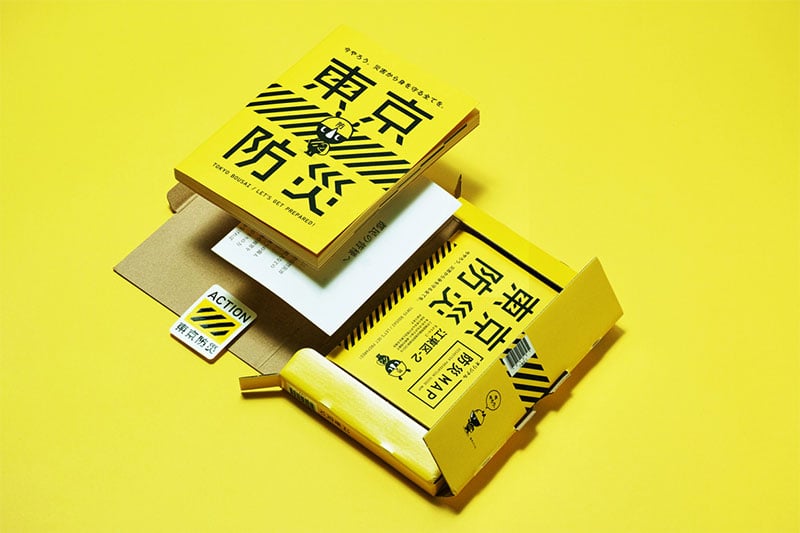

Eisuke trained as an architect and taught himself product and graphic design, but his scope doesn’t end there. Under the mantle of his multidisciplinary design brand Nosigner, he has brought to life projects that lie at the intersection of product design, architecture, and art. The idea that catapulted him into the national consciousness was his disaster information site OLIVE. Next, his practical talents were put on full display with his disaster relief kit ‘The Second Aid’ and manual ‘Tokyo Bousai.’ Gone were the bulky and unappealing feel of standard-issue government items. ‘The Second Aid,’ which resembles a first-aid kit and contains food packs, toiletries, and utensils, is compact and stylish enough to integrate seamlessly into a user’s living space and is regularly spotted on bookshelves across Japan. ‘Tokyo Bousai’ looks less like an earthquake manual than it does a manga comic, coming in bright colours and packed with illustrations that make it not only comprehensible, but actually enjoyable to read.

You might also like: Kodo Nishimura: The Monk in Mascara

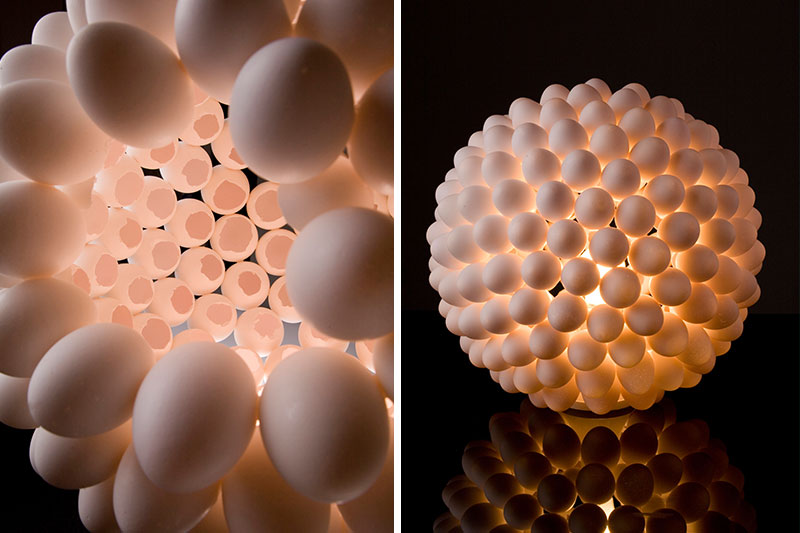

Adding to Eisuke’s list of famous projects are ‘Sachi house’, a cutting-edge welfare facility designed to nurture a sense of community among hospitalised patients and ‘Rebirth,’ an unorthodox lamp created with repurposed eggshells. “When you design, you have to remove your expectations on how things should be. Who knows, a syringe can look like a watch,” he laughs. Today, his products are exhibited at nearly every major design show around the globe from Italy to London, Seoul to Sydney. Currently, he is working behind the scenes with Japanese automobile and electronic giants (the names of which he’s unable to reveal) as well as on a project to improve radioactive waste disposal site designs.

For Eisuke, everything he does anchors firmly in a social context. He sees design and innovation as biological mutations that can ultimately change society for the better. “It’s like iPhones. Each new iPhone model stems from a mutation of its older version, but better,” he illustrates. “Design is a language in that it translates seemingly unrelated concepts and visions into a feasible solution. It’s also a lens through which we can look into our lives and our futures with a whole new perspective.”

Eisuke sees his role as being like a map drawer in society who helps the community understand where they are positioned – and how they should navigate forwards. “A good design can’t just do good for the world. It also has to satisfy a demand and be accessible.” Each of his commissioned projects begins with a ‘Future-Self Workshop’, during which he steps inside his client’s shoes. “I try to dissect and understand the environment, the vision of my clients, their daily habits, or how they interact with their surroundings. I always try to understand what kinds of products might become a hit among consumers. It’s like an anthropological study. What I’m doing is providing tools and strategies and forging weapons. My support enables them to realise their innovative ambitions, or at the very least, make the transition into actualization faster,” he says. “The ultimate goal is to empower and enable.”

You might also like: Preserving the Past with 3D Printing

It’s precisely this capacity to empathise that has made Eisuke’s avant-garde designs so relevant and won him over 100 design awards, including the prestigious Red Dot Design Award and the Good Design Prize. “I’ve always had quite a lot of faith in design. I know that it’s a discipline with more possibilities. Part of me simply wanted to make something really cool, but that simple idea has now led me here,” he says.

When he’s not working on his design projects, Eisuke is an associate professor at Japan’s Keio University. “I want to increase the number of innovators in this world who play a catalytic role in our social development,” explains Eisuke of his involvement. That, and set straight the misconception that innovation can only happen thanks to genius. “Innovating is supposed to be an activity that everyone can pursue, something that everyone is capable of. I, too, have trained myself to become more innovative. I wasn’t always this way. That’s why I’m confident that this is a skill set that can be taught and passed on.”

Related Articles

Kiwami Japan: Japan’s Bizarre Alchemist Turning Tofu into Kitchen Utensils

Society 5.0: Japan’s Next Move to Advance Tech and Science

Startup Lady Japan: The Firm Helping Women Overcome Japanese Work Culture