An abandoned factory on a previously unfashionable side of the Chao Phraya River is the last place you might expect to find a thriving creative community – but then came renowned architect Duangrit Bunnag.

While precision, algorithms and technology are all crucial when it comes to architecture, it takes a whole new level of creativity and courage to transform an existing structure into an upscale complex without compromising its traditional designs, and whilst delivering an entirely new concept to a city. Yet this is something that world-renowned Thai architect Duangrit Bunnag knows all about. He’s the man behind hip creative hub The Jam Factory, and his portfolio includes many award-winning hotels, such as the Hotel de la Paix in Luang Prabang, Laos; winner of Project of the Year at the prestigious World Architecture News (WAN) Interior Design Awards in 2011; and The Naka Phuket in Thailand, which was voted as Wallpaper’s Best New Hotel in 2014. He talks to us about why repurposing old spaces paves the way for the future in his city.

For most, revamping Bangkok’s older buildings for the city’s urban development can be a challenge given the strict local building regulations. For Duangrit Bunnag, one of the most influential voices in Bangkok spearheading this movement, it’s become something of a style signature. Born and raised in Bangkok, Duangrit graduated from Chulalongkorn University with an Architecture degree in 1989 and obtained his Graduate Diploma in Design from London’s prestigious Architectural Association School in 1995. He worked in practices back home before founding his design firm DBALP in 1998. Quickly recognised for his strong lines and modern take, his reputation reached new heights in December 2013 with urban jewel The Jam Factory, and since then, he has become a figurehead for Bangkok’s creative future with an influence that reaches way beyond buildings.

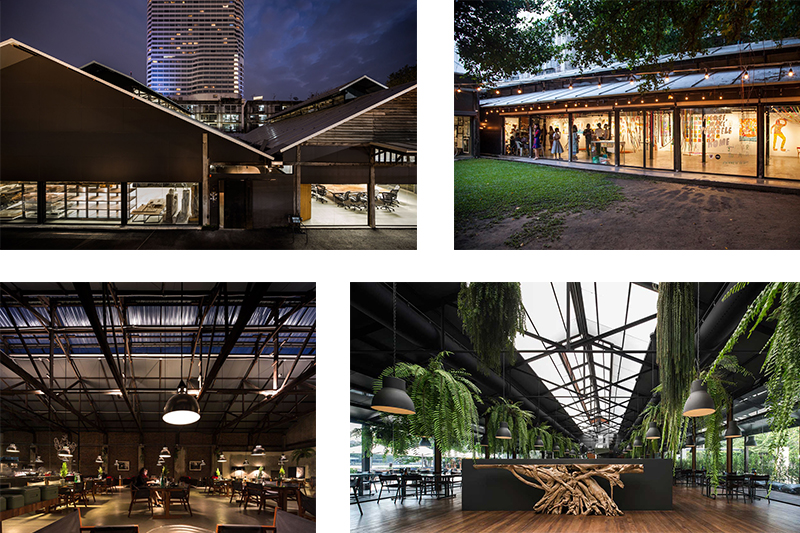

Standing in contrast to the modern complexes along the Chao Phraya River, The Jam Factory has brought a new flavour to the city’s Klong San district, an area that was once home to Bangkok’s oldest stores and residences. Leading the charge for a renaissance on the less fashionable side of the river, the district is now a hub of hot happenings and artsy enclaves – not least The Jam Factory.

The whole idea began 5 years ago when Duangrit discovered a group of rundown warehouses that were once a battery factory. “I saw great potential in the existing structures and wanted to renovate them to create something interesting. It’s also cheaper to renovate old warehouse structures,” he explains. He was looking for a larger space to house his growing team and soon realised that the prospects for a broader project here were endless. “I always say that possibilities lie within the domain of the context. Sometimes, it is best to follow your instincts. The idea of creativity is not about creating something, rather, it’s about eliminating something that blocks you from your creativity.”

In December 2013, the 1600 square metre space was transformed. “At first, we saw the space for our very practice, but after a few months we decided to extend it to the public and named it The Jam Factory.” Today, the complex houses 16 different companies, including the coffee shop The Library, the restaurant The Never Ending Summer and Duangrit’s very own fashion label Lonely Two-legged Creature, which launched more than two years ago, alongside the Candide bookshop, gallery, homewares store and extremely chic riverside bistro The Summer House Project. The decor is all industrial chic, elegant grey walls offset with metal accents, modern furniture, plenty of lush greenery and a fashionably unrefined feel. It is not surprising that within a few months The Jam Factory had shot to the top of any self-respecting hipster’s must-visit list.

The community that gathers around the Jam Factory is growing. Largely made up of young, energetic and creative locals and a substantial amount of tourists from China, Japan and Taiwan, they target their audience – both visitor and vendor – with a clever combination of good retail concepts and affordable pricing. They run a monthly craft market Knack Marke, where young artists and crafters are invited to open up stalls. “The interesting thing about this is that we only charge vendors, THB 500 per day,” says Duangrit. “As a result, we get young artists who would otherwise shy away from testing out their ideas.”

Not one to rest on his laurels, Duangrit’s studio currently has “about 50 architects working on 20 different projects.” Their signature approach is to consider what’s going to happen within a building and the impact that will have, as much as they approach what’s happening on the outside. “Unlike other kinds of architecture that are trying to be something they are not, we are creating an architecture that expresses ourselves,” the visionary explains. And the Jam Factory stands as a representation of Duangrit’s ideology, a space that meets the ever-changing needs of the modern and urban community it serves whilst still preserving the original warehouse characteristics. As he puts it, “after all, a creative space is meant to offer the widest diversity of experiences and inspire fresh thinking.” His latest project with former Elle Decoration editor, Rangsima Kasikranund, is a renovation of a 4000 square meter warehouse with an industrial vibe, which will fully open its doors to the public in October 2018.

Given the architect’s high profile accomplishments, it’s a surprise to discover that all of his projects are self-funded. “The ways we go about doing things are actually five years ahead of their time, and therefore it’s difficult to make investors, financial institutions or the government understand,” he explains. “Support from governmental policies always comes too slowly, and this prevents creative projects like this popping up in Bangkok.” Duangrit’s efforts, however, have not gone to waste. An increasing number of architects and entrepreneurs have been inspired by his approach and now more buildings are being given new life. “We were one of the initial projects that drove the other projects to happen, and as a creator I know I did my job. At least we lit up the fire and people followed.”