Singapore has rolled out a national facial verification scheme, touted as the first in the world.

The biometric technology will allow four million Singaporeans to log onto their SingPass portal via a quick facial biometric check and access hundreds of government and private services online, including healthcare, employment benefits, tax returns, and bank account applications.

The cloud-based face verification solution is intended to improve user experiences and reduce weak security points by eliminating the need to share sensitive information and passwords with multiple organisations. Andrew Bud, founder and CEO at iProov, added, “This pioneering service enables citizens to live in a world of trust online. By iProoving themselves, the people of Singapore can have even greater confidence in their safety, privacy and security on the Internet.”

Aimed at driving the country’s transition into a digital economy under the pioneering National Digital Identity (NDI) programme, the initiative is a partnership between the government and two technology firms – iProov, a UK-based biometric authentication technology provider and Singapore-based Toppan Ecquaria, a digital transformation firm.

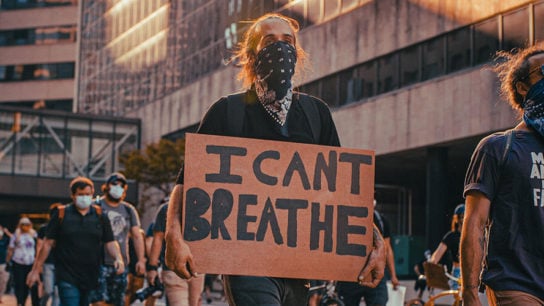

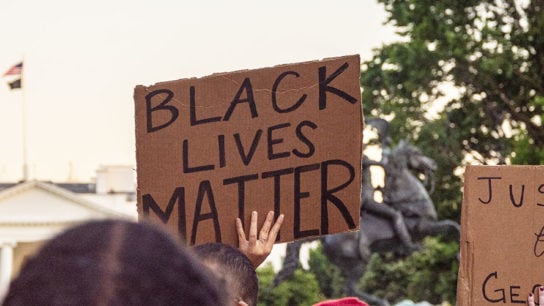

However, the technology touches upon a highly heated global debate over concerns that facial recognition software, when wielded by governments, could infringe personal privacy and lead to mass surveillance and abuse of power – especially when it comes to political threats. During the George Floyd protests earlier in the year, Amazon placed a one-year suspension on police-use of its facial recognition software and IBM halted its R&D efforts in the field entirely, citing worries regarding “mass surveillance, racial profiling, violations of basic human rights and freedoms”.

Addressing these concerns, biometric authentication provider iProov stressed that its technology’s use case was founded on user consent throughout the process. “Unlike face recognition, which matches a physical face seen in a crowd to a list of images on a database, face verification is done with the knowledge and collaboration of the user,” the company’s press release stated.

Nonetheless, sceptics are concerned that the launch of the programme opens the gates for biometric technology to be used to enforce more sweeping powers in the future. “Consent does not work when there is an imbalance of power between controllers and data subjects,” Ioannis Kouvakas, legal officer at Privacy International, told the BBC. Furthermore, existing facial recognition software has been shown to be much less accurate when identifying racial minorities, which could perpetuate systemic prejudices and imbalances.

The Singaporean government has already tapped into its biometric database to enable citizens to make full use of its new facial biometric verification software without additional registration, prioritising convenience over privacy.

Biometric technology has been widely adopted by many governments, such as South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan, as part of a wider contact tracing initiative during the pandemic. However, the national government-sanctioned use of facial recognition has been used much more sparingly.

The US’s controversial Biometric Exit initiative, which has already been launched in Los Angeles, plans to integrate facial recognition technology at all major airports by 2023. China has also implemented widespread facial recognition software in major cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen to enforce petty theft and dole out fines. However, the nation has been criticised for using facial recognition software to enforce mass surveillance, enact behavioural engineering, and target and detain Uyghur Muslims in an act of racial profiling.

Related Articles

Microsoft AI’s Racial Blunder Highlights Systematic Prejudice in Tech