TED fellow Kotchakorn Voraakhom is saving her home Bangkok from the ravages of climate change. An architect by trade, she founded Porous City Network, a green initiative that’s caught the attention of the UN.

Harvard graduate Kotchakorn Voraakhom is creating urban solutions for sinking cities. As the founder and CEO of Bangkok’s green initiative Porous City Network (PCN), she is working together with communities to reduce the impact of flooding, putting her background in landscape architecture to good use. “Many Southeast Asian cities – especially in Thailand – are sinking,” she explains. “Flooding is a normal phenomenon in Delta cities where the land is porous, but when you combine this with heavy development, the land can no longer breathe.” Forbes, the United Nations and TED Conferences around the world have all recognised Kotchakorn’s groundbreaking work, and she was named a TED fellow earlier this year. Together with a proactive multi-disciplined team, her enterprise Porous City Network is paving the way for a healthier ecosystem that balances urban development alongside environmental stressors.

Growing up amidst Bangkok’s yearly floods, Kotchakorn has seen first-hand the devastation flooding leaves behind, whether in the form of electricity shortages and sewer-contaminated drinking water or large-scale evacuations and outright displacement – damage that has only worsened with Bangkok’s urbanisation over the last three decades which has encroached heavily upon agricultural floodplains. “When I was younger, it was so much fun. You had your own boat and the street turned into a canal,” she relates of her childhood. “But the older I became, the worse it’s got because we’ve just developed our cities how we want without any of these concerns.” As a landscape architect, Kotchakorn is equipped with the skills to address the growing needs of Bangkok’s population of 10 million, and she is determined to be a part of the solution rather than the problem.

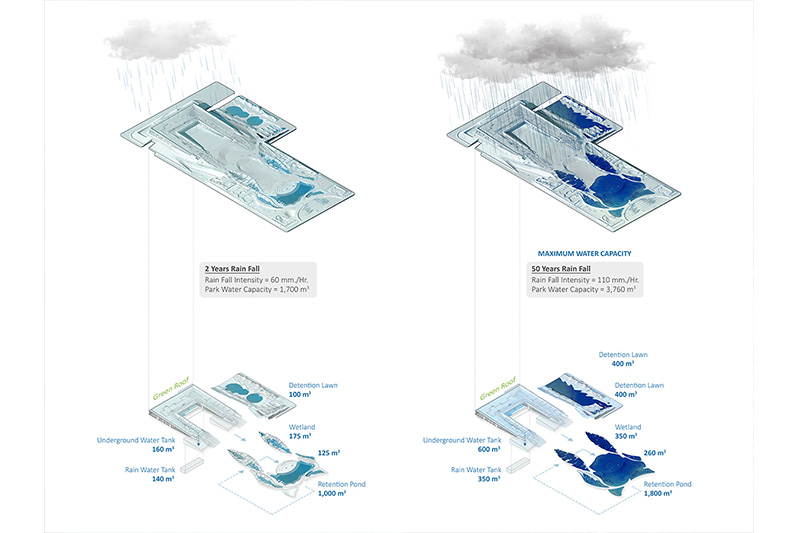

Last year, Kotchakorn unveiled the stunning Chulalongkorn Centennial Park and Avenue in the heart of Bangkok, an 11-acre flood defence project – built on land valued at over USD 700 million – that offers the vibrant city some much-needed green urban infrastructure. Designed to contain over a million gallons of water, the park utilises water-retention techniques, integrating a green roof, retention pond, detention lawn, wetlands and underground water tanks to protect the urban jungle. While the park is only a small step towards the fully fledged flood defence network that Bangkok needs, it is a shining emblem of what the future could look like with the help of urban city planners, engineers and architects.

Given the widespread problem of sinking cities across Southeast Asia, Porous City Network has expanded its reach to other cities, travelling to Malaysia to work with communities in Penang where George Town, a UNESCO heritage site, is sinking. Next year, Kotchakorn plans to travel to Jakarta with volunteers and students to establish an even wider network. Taking a bottom-up approach, Porous City Network is laying the groundwork essential to tackling Southeast Asia’s flood management needs.

“When life gives you floods, you work with it,” Kotchakorn laughs. She believes the way forward for Delta cities is to integrate holistic solutions such as green infrastructure that adapt to their specific environmental conditions. “You can’t just copy the sea wall in the Netherlands, for example. That would destroy Bangkok’s ecology. Unlike them, we have beaches, wetlands and mangroves.” Instead, she advocates more collaboration-based learning across Southeast Asia. “The voices of communities across Southeast Asia have similar rhythms across different languages. We need to come together and solve this problem from the bottom up – not just from the top down.”

Although a number of challenges still stand in the way of tangible progress, Kotchakorn remains focused on her goal to improve Southeast Asia’s flood resistance. “Climate change isn’t happening in 20 years. The city is sinking now. The impact is happening right now,” she stresses. “We need governments, communities, and every viable project to be concerned and obligated to address the climate risk factors.” Although the Thai government has pledged close to USD 800 million to 28 flood protection projects, the population remains uncertain that state policies will address long-standing issues given Thailand’s political instability. Right now, the government’s policies don’t always necessarily address the real need, she explains, and it is up to communities to pour their time and energy into finding solutions. As an architect and a citizen, she herself is doing everything she can to make a difference. “You have to push every single possible opportunity at the same time, and see what arises in five years. But never stop. Just do it.”